In contrast were the delights of experimenting and thinking in the little chemical lab I set up at home, and here, on a weekend, I might spend an entire day in happy activity and absorption. Then I would have no consciousness of time at all, until I began to have difficulty seeing what I was doing, and realized that evening had come. When, years later, I read Hannah Arendt, writing in "The Life of the Mind" of "a timeless region, an eternal presence in complete quiet, lying beyond human clocks and calendars altogether . . . the quiet of the Now in the time-pressed, time-tossed existence of man. . . . This small non-time space in the very heart of time," I knew exactly what she was talking about.

There have always been anecdotal accounts of people's perception of time when they are suddenly threatened with mortal danger, but the first systematic study was undertaken in 1892 by the Swiss geologist Albert Heim; he explored the mental states of thirty subjects who had survived falls in the Alps. "Mental activity became enormous, rising to a hundred-fold velocity," Heim noted. "Time became greatly expanded. . . . In many cases there followed a sudden review of the individual's entire past." In this situation, he wrote, there was "no anxiety" but, rather, "profound acceptance."

Almost a century later, in the nineteen-seventies, Russell Noyes and Roy Kletti, of the University of Iowa, exhumed and translated Heim's study and went on to collect and analyze more than two hundred accounts of such experiences. Most of their subjects, like Heim's, described an increased speed of thought and an apparent slowing of time during what they thought to be their last moments.

A race-car driver who was thrown thirty feet into the air in a crash said, "It seemed like the whole thing took forever. Everything was in slow motion, and it seemed to me like I was a player on a stage and could see myself tumbling over and over . . . as though I sat in the stands and saw it all happening . . . but I was not frightened." Another driver, cresting a hill at high speed and finding himself a hundred feet from a train which he was sure would kill him, observed, "As the train went by, I saw the engineer's face. It was like a movie run slowly, so that the frames progress with a jerky motion. That was how I saw his face."

While some of these near-death experiences are marked by a sense of helplessness and passivity, even dissociation, in others there is an intense sense of immediacy and reality, and a dramatic acceleration of thought and perception and reaction, which allow one to negotiate danger successfully. Noyes and Kletti describe a jet pilot who faced almost certain death when his plane was improperly launched from its carrier: "I vividly recalled, in a matter of about three seconds, over a dozen actions necessary to successful recovery of flight attitude. The procedures I needed were readily available. I had almost total recall and felt in complete control."

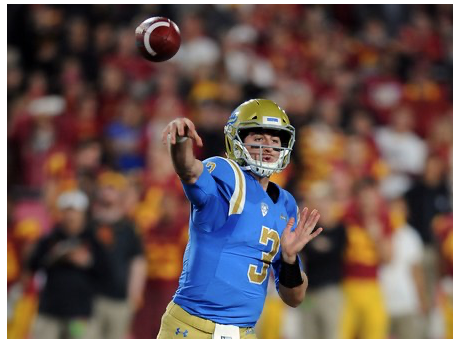

Many of their subjects, Noyes and Kletti said, felt that "they performed feats, both mental and physical, of which they would ordinarily have been incapable." It may be similar, in a way, with trained athletes, especially those in games demanding fast reaction times. A baseball may be approaching at close to a hundred miles per hour, and yet, as many people have described, the ball may seem to be almost immobile in the air, its very seams strikingly visible, and the batter finds himself in a suddenly enlarged and spacious timescape, where he has all the time he needs to hit the ball.